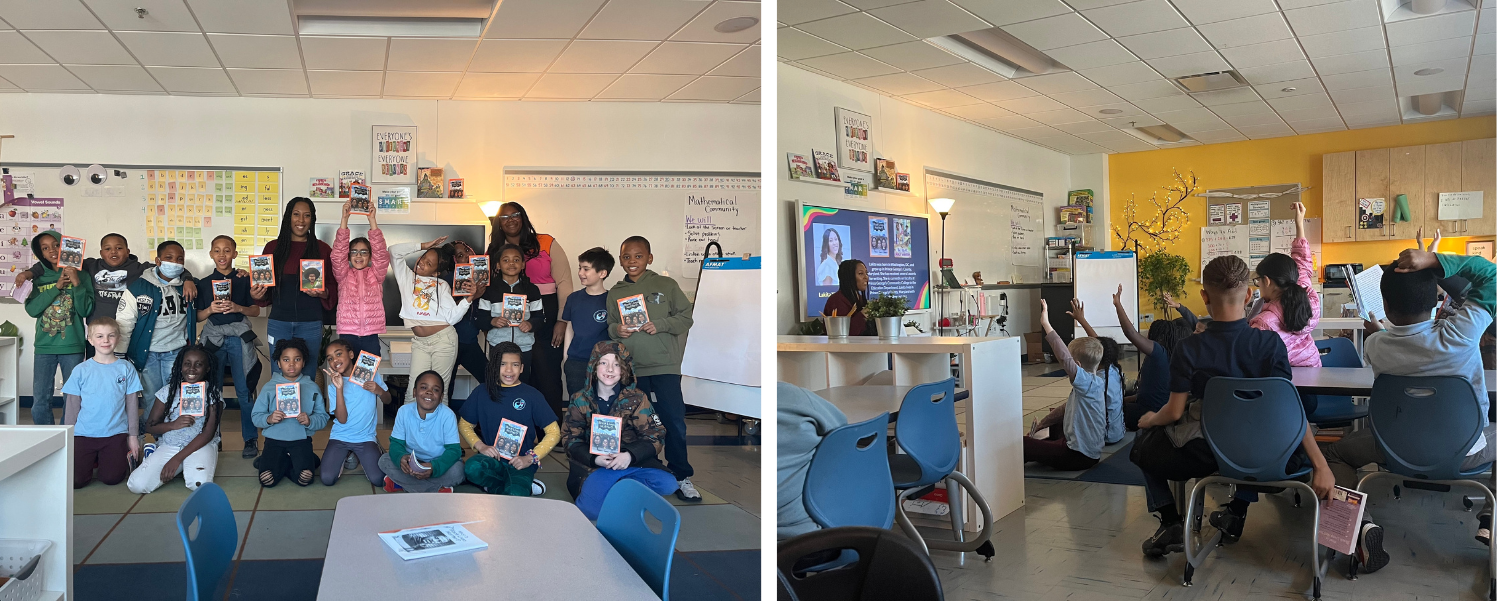

Lakita Wilson sits on a chair in the front of the classroom, surrounded by a dozen third graders at her feet. The children are transfixed by her, listening as she explains the history of the Black Lives Matter movement, how it was ignited by the death of an innocent Black teenager, and how it grew in scope with every tragic death at the hands of police violence.

The content of the presentation contrasts starkly with the room in which it is being given. There is a gentleness to the yellow accent walls, a serenity in the house plants swaying by the door, a warm glow emanating from the fairy lights and floor lamps in every corner of the room. The teacher, Ms. Sarvis, has carefully curated a space in which her students can feel at peace. Here, children are treated as children, with all the love and affection they need to grow.

“Does anyone have any questions?” Lakita asks, and immediately a flurry of hands shoots up toward the ceiling. The stillness has suddenly been replaced with fervent curiosity. The children squirm on the navy blue rug, eagerly waiting for their chance to ask the author their own burning question.

One student asks the inevitable question: “What inspired you to write this book?” At first, Lakita’s response is uneventful. She shares that after the death of George Floyd in the summer of 2020, a publishing company reached out to her, asking her to write about Black Lives Matter in the wake of its resurgence. She accepted the offer, but not just for money or the excuse to publish another book. Lakita, a Black woman who grew up in the DC area, felt deeply connected to the movement.

“How much do you care about the Black Lives Matter movement?” a student asks.

“Because I know people who have been harmed by police,” Lakita responds. “It’s always been something that’s been very important to me.”

She shares that many years ago, at a party she was attending in high school, a friend of hers was shot and killed by a police officer. The students gasp, overtaken with new impassioned energy. Even if someone was committing a crime, one student shouts out, that doesn’t mean they get shot! Out of the collective murmur, I hear …killing people left and right from someone else on the rug.

Once the chatter dies down, Lakita calls on another: “Why didn’t you write about your friend?”

To children, writing a book is an act of total creative control. Lakita has to explain that, since she was commissioned by a publisher, she had to follow their rules. With a mere 4000 words to work with, she could only focus on the victims of police brutality that became the most well-known, the ones who played the greatest role in starting, spreading, and sustaining the movement.

The students return to that sense of serenity. Below a sign that reads Everyone’s Different, Everyone Belongs, Lakita receives one final question: “How did you feel after writing the book?”

She pauses for a moment, takes a breath, and looks at the innocent young faces at her feet.

“Sometimes I worry about coming to schools because I don’t want to make students sad or nervous. And it was pretty heavy, sad information to research.”

A few children nod their heads.

“But it was just that important to me that I was willing to read the information and be a little sad while I‘m writing it so I get the word out,” she says, closing her copy of the book. “I thought it was important to share that with students too.”

I tell the students that we have run out of time for more questions. Suddenly, they are excited and enthusiastic children again, asking Lakita to sign their books, posing for the photos I take, and excitedly talking among themselves, still starstruck in the presence of the author.

Soon, they will continue to their next subject, another day in the quiet contentment of third grade, in the childhood they so fully inhabit.

Lakita Wilson visiting Van Ness Elementary School as part of this year’s Black Lives Matter Week of Action.